With the UK entering a deep recession, policymakers have been forced to consider unprecedented measures in order to support the economy through the coronavirus crisis.

Initiatives such as the ‘furlough’ scheme and widely available mortgage payment holidays would have been unthinkable just a few months ago. And now, the Bank of England is also considering negative interest rates for the first time in its 326-year history.

Giving evidence to the Treasury Select Committee in May, Governor Andrew Bailey said negative rates were under “active review” by the central bank. He added: “We have been looking very carefully at the experience of those other central banks that have used negative rates.”

So, what are negative interest rates? Why are they necessary? And what might they mean for your savings and mortgage?

What are negative interest rates?

If a country’s central bank sets its Base rate below zero, high street banks must pay to deposit cash with it. It is designed as an extreme measure to encourage banks to lend more money, and consequently to stimulate the economy.

In an economic downturn, individuals typically hold onto their money and wait to see some sort of improvement before they decide to spend again. As a result, deflation can become entrenched in the economy.

People stop spending, demand for goods and services declines, prices fall, and people wait for even lower prices before spending. It’s a cycle that can be very hard to break.

Negative rates tackle this issue by making it more expensive to hold onto money, and by incentivising spending. The theory is that negative interest rates would make it less appealing to keep money in the bank as, instead of earning interest on their savings, they could be charged a fee by the bank to hold their cash.

Simultaneously, negative interest rates would make it more appealing to borrow money, since it would push loan rates to rock-bottom lows.

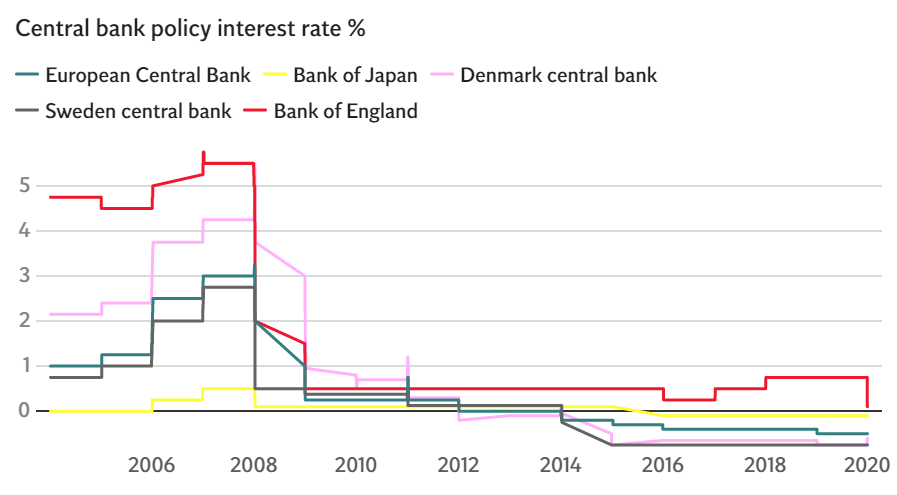

Other countries have already adopted a negative interest rate policy. Sweden, Japan and Denmark already have negative rates, while the European Central Bank deposit rate is -0.5%.

Source: Independent

Mortgages

Most of the mortgages taken out in the UK in recent years have been on fixed rates. So, if your home loan is on a fixed rate of interest, you won’t see any change to your monthly repayments even if rates were to become negative.

If you have a mortgage that is linked to the Base rate, or to your lender’s Standard Variable Rate (SVR) then it is possible that you will see a reduction in your repayments if rates were to fall again.

A word of caution, however. Most lenders have clauses in their terms and conditions which mean their mortgages have a ‘collar’ below which mortgage rates cannot fall. For example, Nationwide will never reduce the rate it tracks below 0% – so if your mortgage is at Base rate plus 1%, it will never fall below 1%.

In Europe, some banks have offered remarkable deals. In 2019, Denmark’s third-largest lender, Jyske Bank, offered a 10-year loan with a -0.5% annual rate. Essentially, at the end of the term, you owed less than you had repaid. Finland’s Nordea Bank offered 20-year mortgages at 0% interest last year.

While it is possible, it is unlikely that mortgages in the UK will be offered at negative rates. However, the cost of borrowing could still fall. In May, financial analysts Moneyfacts reported that the average rate on two- and five-year fixed mortgage deals had a level not seen since Moneyfacts’ electronic records began in July 2007.

Savings

It has been a tough few years for savers. Interest rates have been at rock bottom for a decade and, in the three months since the Coronavirus pandemic began impacting the UK economy, the average rate on an easy access account has halved, from 0.60% on 11th March 2020 to 0.30% on 1st June.

A move to negative interest rates is likely to see interest rates reduce even further. However, evidence from abroad shows that banks and building societies have been reluctant to charge savers to hold money in their own accounts – even if they are being charged by a central bank.

Christina Nyman, chief economist at Swedish lender Handelsbanken, says charging savers to put money in their own accounts is seen as “taboo” in Sweden. She says: “Competition is fierce, and households are ready to move their money to another bank, so nobody wants to lose business.”

Negative interest rates could, however, result in banks charging wealthier clients for holding their savings.

In 2019, Jyske Bank introduced negative interest rates for customers who held balances over $1.1 million. These savers were charged 0.6% annually to hold their money in the bank. Last year also saw UBS start to charge its high net worth clients a fee for cash savings of more than €500,000 (£449,000), starting at 0.6% a year and rising to 0.75% on larger deposits.

Andrew Hagger, the founder of the financial information website Moneycomms, said: “It could be that super-rich clients in the UK get charged a similar fee as the commercial banks may wish to discourage large cash holdings which they are having to pay for.”

Charging clients to hold their savings brings its own issues. In Germany, where some banks impose charges on deposits of more than €100,000 (£90,000), some people have started stashing their money in vaults.

According to Germany’s central bank, physical cash holdings by families and businesses there have almost trebled to €43.4bn since the European Central Bank (ECB) introduced a negative deposit rate in 2014.

But David Oxley at Capital Economics says that putting cash in a vault “runs the risk of the money either being lost, stolen, or damaged,” he says. “Bank deposits cannot catch fire, but banknotes can.”

The potential downsides of negative interest rates

One of the factors the Bank of England is considering before a move to negative interest rates is that they hit bank earnings by squeezing the gap between the money they make on loans and what they pay to savers.

“If not passed on to customers, negative rates would hurt bank profitability, especially at a time when they are expected to be hit by crisis-related loan losses,” says Danae Kyriakopoulou, chief economist at the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum (OMFIF).

Negative interest rates are a particular challenge for building societies, which hold around £1 of every £5 in British savings accounts.

While commercial banks can access cheaper borrowing by tapping financial markets, building societies must raise at least half their funding from individual savers.

Get in touch

If you’re concerned about low interest rates and would benefit from the help of a financial planner, please get in touch. Email info@blueskyifas.co.uk or call us on 01189 876655.