In tune with most other administrations around the world, the UK government has acted with speed and scale to try and limit the worst effects of the coronavirus. Substantial measures supporting the economy were announced when it became apparent that the consequences of lockdown could be severe and long-lasting.

Consequently, it is predicted that government debt may exceed £2 trillion by the end of this year. Over £200 billion of new borrowing could be needed. But where does the money come from and what could be the long-term impacts?

How the government borrows money when supporting the economy

When the government spends more than it receives in revenue (mainly taxes) it has to borrow. This is sometimes referred to as the government’s budget deficit.

Over 85% of the government’s total debt has been raised by selling gilts and bills, mainly to financial institutions. Just under 10% is raised from National Savings and Investments (NS&I), the government-owned savings bank. Other sources make up the remainder.

Gilts and bills are ways of loaning money to the government. A buyer of a gilt lends the government money for a specified length of time. In return, the holder of the gilt receives an interest payment. When a gilt matures, the government pays the original amount loaned back to the holder of the gilt. Gilts are traded on secondary markets by investors, pension funds and other institutions.

Insurance companies and pension funds are the biggest holders of gilts and bills with around 32% of the total value. A further 28% are held overseas.

Since 2009 the Bank of England has become a large holder of government debt – by September 2019 it held 23% of the value. The Bank of England has been purchasing gilts as part of its quantitative easing programme which aimed to provide a boost to the economy following the 2007-2009 financial crisis. The Bank is returning to this approach in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

The Bank of England’s gilt purchases mean debt interest costs are lower than they would otherwise have been. The effective interest rate paid on this debt is the Bank’s main interest rate – known as Bank Rate – which is lower than the interest rate due on the gilts.

The Bank’s decision in March to cut Bank Rate to 0.1% (from 0.75%), immediately lowered the effective interest the government pays on gilts held by the Bank.

Markets continue to invest in gilts which are seen as some of the safest assets around. The Bank of England’s purchases have helped to increase demand for gilts. The demand for gilts tends to push up the price of gilts and thereby reduces the interest payable. This has the following immediate consequences:

- If you are looking to buy an annuity (a fixed income for life) then the rate being offered is likely to be lower, as gilt yields play a big role in determining annuity rates. Therefore, you would need a larger pension fund to purchase the same level of income. You may need to rethink your plans.

- If you are a member of a final salary pension scheme, the transfer value offered by the scheme may have increased during the crisis, as pension funds need to purchase more gilts to back the scheme liabilities.

The long-term implications of this government borrowing on your finances

There are other longer-term issues that could arise. For example, interest rates on cash savings are now even lower than they were two months ago and may not be getting back to ‘normal’ any time soon.

According to financial analysts Moneyfacts, the average easy access savings rate fell from 0.56% in March to 0.44% in mid-April. Cash in savings accounts is therefore likely to continue losing value in real terms (i.e. when inflation is considered).

In addition, the reduction on interest paid on government gilts now makes other asset classes (i.e. equities) more attractive. Despite the large swings in value seen over the last few weeks, equities are likely to outperform cash over long periods of time.

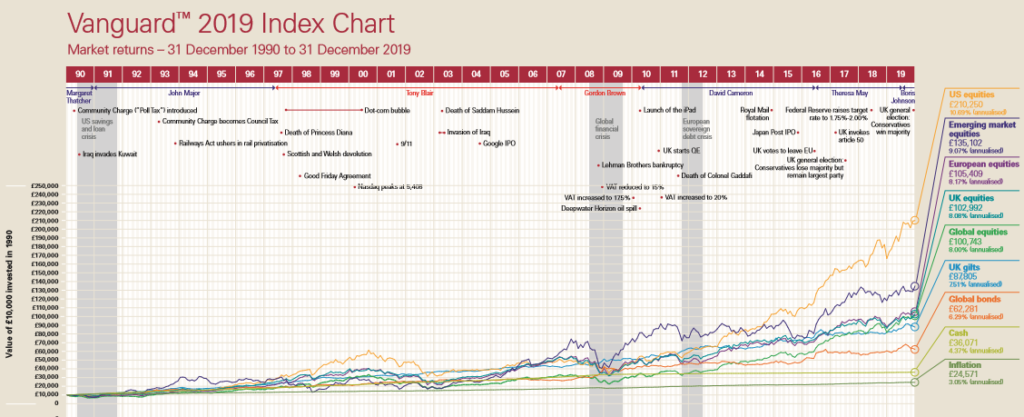

The chart below shows what £10,000 invested in 1990 in a range of investments, including UK equities and cash, was worth at the end of 2019.

Despite many volatile periods – the dot.com bubble, the global financial crisis, the Brexit vote – £10,000 invested in UK equities in 1990 was worth £102,992 on 31 December 2019, equivalent to an 8.08% annualised return.

Compare this to cash, where £10,000 invested in 1990 grew to £36,071 during the same period – a 4.37% annualised return.

Notes: Cash = ICE LIBOR – GBP 3 month; global equities = the MSCI World Index; US equities = S&P 500; UK equities = FTSE All-Share; inflation = Retail Price Index, (Jan 1987=100); global bonds = Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate; European equities = MSCI Europe; UK gilts = ICE BofA; UK gilt (local total return) emerging market equities = MSCI emerging markets; all shown gross of taxes and of fees and in GBP.

Source: Bloomberg and Factset and Bank of England, as at 31 December 2019

Finally, the additional borrowing required by the government in supporting the economy is likely to lead to higher taxes in the future. Making the most of tax-breaks afforded to pensions and some other investments will be even more important.

We consider this more here, where we take lessons from the aftermath of World War II to predict what may happen to taxes in the next few years.

Get in touch

If you would benefit from a financial review, please get in touch. Email info@blueskyifas.co.uk or call us on 01189 876655.

Please note

The value of your investment can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount you invested. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.